Aid Flows to Forests

Because of my work for the European Commission, I was soon regarded as a global ‘expert’ on tropical foresty aid – even though I hadn’t seen a single such forest through this work!

A lovely Canadian at UNDP asked me to undertake another project - to measure global financial flows to forestry. There was an intergovernmental conference due to be held in 2000, and donors wanted an update on progress since the Rio Earch Summit in 1992.

I already had established some data on European Commission funded projects, and some other agencies. I was also good at talking people at different organisations into sharing information. I started with these sources, and started to identify other key players, and fill in the gaps.

I spent an extraordinary two week period working in London, Paris, Rome, Washington and New York. On the surface, it looked like I had finally established myself in the sector, and was doing meaningful and important work. The reality was more complex.

Much of my work was quite solitary and isolated. The travel sounded glamourous but was lonely and stressful. I also saw signs everywhere of how ultimately useless my work would be. There had been many other attempts to understand global aid flows in the past – I came across them gathering dust, forgotten, in a basement in Rome. At one point I circulated my initial estimates, but accidentally doubled them, because of a basic spreadsheet error. Nobody noticed.

Forestry aid was also a particularly unfortunate sector to start in. Long project time-scales, competing economic interests and political issues make projects contentious. The economic pressures on forest resources are vast and immediate, while environmental concerns lack much leverage on the ground.

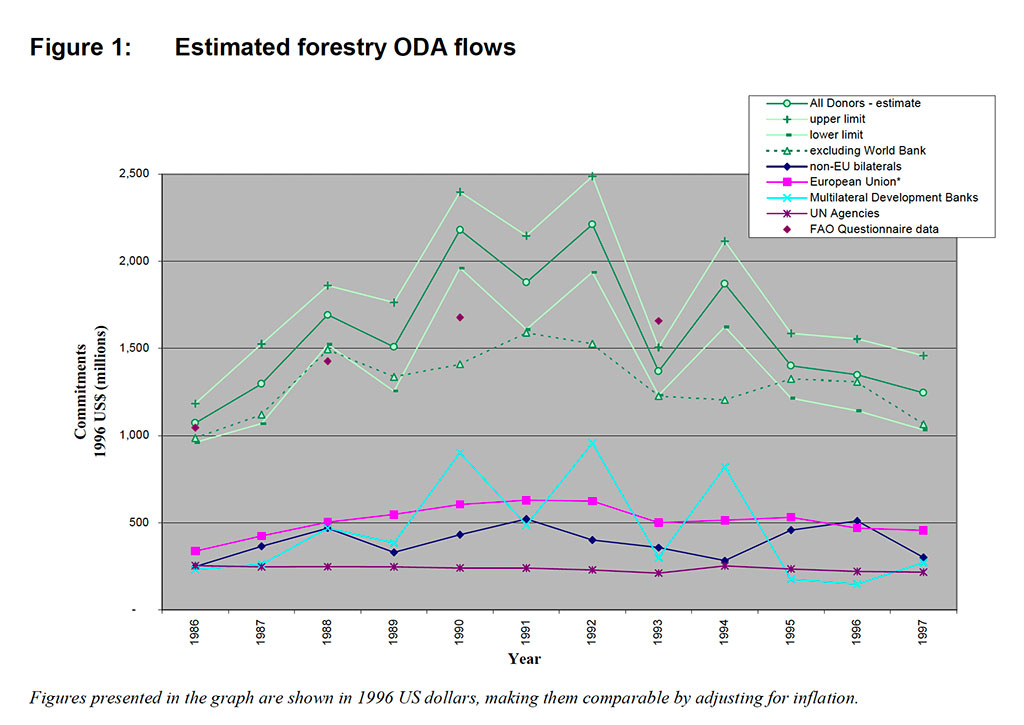

My final figures had to include rough estimates, and be corrected for various currency fluctuations and inflation. They showed an increase in ODA (Official Development Assistance) after the Rio commitments, but which had reduced in more recent years. This was useful evidence for the intergovernmental conference.

My report was presented at the UN in New York, during IFF4. It was an interesting but frustrating process to watch the sessions. Different countries were drafting wording for resolutions, and there was a lot of subtle politics behind the scenes. It was fascinating but not particulary edifying.

Despite doing a good job on two major projects, I was not getting any further work – and the ODI did not really know what to do with me. I was left drifting when my contract ended. (Years later, my manager at the time apparently apologised to a friend of mine, for how I was treated!)

In any case, I think I realised I would not be happy working in conventional aid and development as a sector. My instincts had already been alerted by what I saw in the Balkans as a student, and later by my experiences in Africa. There are some really good people working in the sector, but they are often quite impotent and frustrated. The real pressures, and potential for changes, lie elsewhere.

My full report is here. Looking back over it, almost a quarter of a century later, I do not remember much of the details. The scale of the task was huge, and I had very little support. I am proud of what I achieved, given those challenges.

At that time, Claire Short's DfID was challenging the 'tied aid' system of previous adminstrations, where money to countries in need was contingent on buying supplies and paying staff from the donor country. She instituted a clearer focus on poverty and effectiveness, which had not always been the case. Sadly, we are now returning to that previous era with British aid.

My work on forestry aid was groundbreaking. There remains little transparency in the sector.

⥢

⥢

⥤

⥤